January 2, 2015

By James Greif

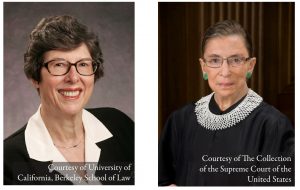

The AALS Section on Women in Legal Education is honoring Herma Hill Kay, University of California, Berkeley School of Law with the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Lifetime Achievement Award. Justice Ginsburg is scheduled to present the award named in her honor at the section’s luncheon on Saturday, January 3, 2015 from 12:15 p.m. – 1:30 p.m. Professor Kay is being recognized for her outstanding impact and contributions to the Section on Women in Legal Education, the legal academy and the legal profession throughout her career. Justice Ginsburg and Professor Kay are lifelong friends and colleagues and both took time out of their busy schedules to discuss their experiences with AALS and as some of the first women professors in the legal academy.

Q: Justice Ginsburg and Professor Kay, can you discuss how the two of you became friends and colleagues leading up to your casebook on sex discrimination in the early 70s?

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: I first met Professor Kay at a conference on women and the law at Yale Law School. I knew about her—among other things she is a leading expert on conflict of laws. I was teaching conflicts at the time and using a casebook that she co-authored. And when we met at the Yale conference I think it was chemistry between the two of us; I liked her enormously from our first meeting.

Herma Hill Kay: Yes, actually we got together to write a casebook. The original version of that casebook came from our co-author, Kenneth Davidson, who had worked on a set of materials dealing with women and employment. He sent it to me to see if I’d be interested in adding something on family law, and of course I was. We decided that we needed someone to do a constitutional law chapter for the book and we both immediately thought of Justice Ginsburg, who was then a law professor. She was co-sponsoring a conference on law school curriculum. The question there was whether you ought to have special courses devoted to women’s rights or whether you ought to have bits and pieces of that subject matter put into every course, like Contracts, Torts, Property and so on. The argument in favor of doing the latter was that you would reach many more students than if you just had a standalone course. At the end of the meeting, Ginsburg and Davidson and I decided that we would do a standalone book. That’s how our collaboration came about and that was the beginning of our friendship.

Q: Justice Ginsburg, you were also a founding member and early leader of the AALS Section on Women in Legal Education. Can you talk about what the AALS and the section meant to you at a time when there were not very many women professors in the academy?

RBG: The Women in Legal Education Section started out as a committee that AALS wasn’t ready to yet recognize as a section. Our principal effort was to see that there was a genuine non-discriminatory policy at AALS. There was at the time, one law school, Washington & Lee, that was all-male. Part of the effort was to see that gender, like race, would be a prohibited basis for excluding anyone from law school. We took a survey of women in teaching positions at law schools and the result was not what you would want it to be. But just being conscious of the problem spurs change. We did that, and there was an effort to persuade law schools that they ought not only to have a course on women and the law, but include across the curriculum issues that concern the treatment of women by the law. I think our efforts were to see that there was an open-door policy for the admission of women as students, that law schools made a greater effort to hire women faculty, and that the teaching curriculum included issues relating to gender in all courses, not simply one course on women and the law.

Q: Professor Kay, can you discuss what the landscape was like during the founding of the AALS Section of Women in Legal Education?

HHK: [Justice Ginsburg] helped found the Section on Women in Legal Education. In my early days, I never went very often to AALS meetings. I think I remember one meeting (shortly after I joined the Berkeley faculty) that was held at the Edgewater Beach hotel in Chicago. I didn’t really have a lot of interest in the organization at the time because I was busy with things out here on the West Coast. That was the case until Sandy Kadish said that the nominating committee wanted me to consider being nominated for president-elect, to be of course followed by president and then immediate past president. And I had little experience with the AALS at that point, but they thought that it would be a good way to get me involved.

When I was president of the AALS [in 1989], I worked very closely with many of the sections, including the Section on Women in Legal Education, but I was never an officer or chair of that section. My more recent engagement in it has been around the oral history project that they’ve begun. I was only the third woman president of the AALS, Soia Mentschikoff being the first and Susan Prager being the second. It was quite a new experience and it was only in working on this book on the history of women law professors that I realized that between 1900 and 1960—which is when I joined the Berkeley faculty—there were only 14 full-time women professors tenured or tenure-track at any law school in the country. And in the 1960s there were only 35 more. It grew very slowly at first, but in the 70s, the hiring of women increased. I think AALS was one of the first professional organizations to say that you could not discriminate on the basis of sex as part of membership. That sort of set the stage for a lot of law schools trying to, as Soia Mentschikoff bravely put it, find “their woman.” That’s when Ruth [Ginsburg] went to Columbia in 1972 as their first tenured woman law professor.

Q: Can you talk about some of your favorite memories or contributions to the AALS and the section?

RBG: The meeting when they voted to establish that gender would be a prohibited classification for exclusion, that meeting I remember very well. I think Washington & Lee was pleased that the AALS made this effort. The law school wanted to admit women, but they were part of an all-male university at the time. They could go to the university and say, “We can’t remain members of AALS unless we admit women.” I think that was a very good result. My experience with AALS was certainly positive in seeing this committee on women in legal education be recognized as a full section of the association. I was also on the Executive Committee for one year [in 1972]. In the beginning, there were so few of us in law teaching. [The AALS Annual Meeting provided] the opportunity to get to know each other and to compare notes on what our experiences were in our law faculties and what we could learn from each other about ways to advance women’s stature in law teaching.

HHK: I remember very fondly those morning breakfasts when we didn’t really have a formal program. We exchanged notes and gossip and it was really kind of a mentoring session for the younger women. Because there were so few law schools that had more than one or two women professors, they didn’t really have a great deal of opportunities for mentoring. Of course, those were the days before listservs and email. You really either had to get on the phone and talk to someone long distance, or you had to go to regional meetings which were held around the country. But it was the AALS Annual Meeting that really was the “drawing card” for women professors who were then able to interact with those who arrived in the academy before them, and in turn help the women who were coming after them.

Q: Professor Kay, you have written extensively on Justice Ginsburg’s contribution to women’s rights under the law. What has made her an effective scholar and leader in this area?

HHK: I think the bottom line—leaving aside for a minute her extraordinary intelligence, her great sense of strategy and all that—is that she is so completely over prepared for everything she does that it’s incredible to watch. I’ve watched her do oral arguments before the Supreme Court when she was arguing cases on behalf of the Women’s Rights Project for the ACLU, and there was not a single question that anybody asked her that she didn’t have answers to. She thought of it all in advance. She understands how to put herself in the shoes of the other side and prepare to beat their objections as well as putting forward her own case. And then when she did get a really tough question, she always answered very calmly, very quietly. I never heard her raise her voice and she hardly ever moved from the podium. She would use a kind of very quiet observation that was just devastating to the other side. And you can translate that to what she does now on the Supreme Court when she’s asking questions of counsel who appear before her. More often than not, she goes right to the heart of the issue before anybody else does.

Q: Justice Ginsburg, the same could be said of Professor Kay. In your opinion, what has made Professor Kay an effective advocate and scholar in advancing women’s rights and the standing of women in legal education?

RBG: One, is that she was so well-respected in the legal then-fraternity that if she was in favor of something, that carried weight. I think she was the second women appointed to Berkeley. Barbara Armstrong was probably the first woman in a tenure track position in any law school and Herma had a very close relationship with Professor Armstrong. At the time, Herma was the co-author of the Uniform Marriage and Divorce Act (UMDA). Her specialties were conflict of laws and family law. And I think for the students at Berkeley she taught by example that a women could be a respected legal scholar and still— Herma was a very stylish person, she drove a yellow Jaguar back and forth to Berkeley, she had a pilot’s license, and she was exceedingly well-dressed. I think the students could see that it was okay to be a woman, to be yourself, not try to be a man and yet succeed.

Q: What does it mean to you that the AALS award that bears your name will be presented to your close friend and colleague Professor Kay?

RBG: First, I’m touched that the AALS would want to have an award in my name. And I couldn’t imagine anyone in the world I would rather have receive this award than Herma Hill Kay. She’s a grand human in all respects. I should say something else about Herma. I’m not sure if she still does this. She’s a well-disciplined person and she swam—that was her form of exercise. I think she did it almost every day.

Q: And what does it mean to you, Professor Kay, as a friend and colleague of Justice Ginsburg, to receive the AALS Section on Women in Legal Education award which is named in her honor?

HHK: It’s just so wonderfully marvelous to have her name associated with it. I think it makes it the most precious award I’ve ever received. I certainly will treasure it forever. I’m especially delighted that Justice Ginsburg is not only going to be at the presentation, but that she’s actually the one who is going to present it to me. That will really be a special treat.

This article originally appeared in the 2015 AALS Annual Meeting Newspaper