A lawyer for the prosecution came to the rescue of a prisoner on death row on Monday in a dramatic twist to a US supreme court case described as one of the most egregious cases of courtroom race discrimination seen in decades.

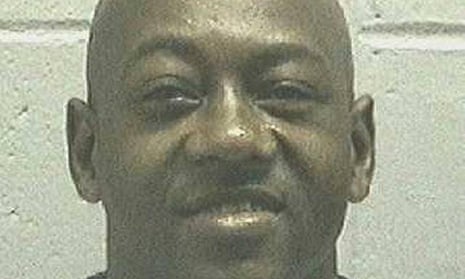

Timothy Foster, a black teenager who confessed to the murder of a white woman in Atlanta in 1986, is appealing his death sentence after legal notes subsequently emerged that revealed how all the black jurors at his sentencing were singled out and excluded from the jury.

But despite a sympathetic reception when the case finally reached the US supreme court after 29 years, Foster’s appeal risked immediate collapse when chief justice John Roberts surprised court-watchers by questioning whether he had the power to order a retrial in the case.

More than half of the opening argument from veteran civil rights lawyer Stephen Bright was taken up as he struggled against Roberts’s technical challenge, which suggested the case should merely bounce back to the Georgia supreme court rather than be overturned.

Georgia’s deputy attorney general, Beth Burton, who was meant to be arguing against the appeal, appeared to help put Foster’s hopes of avoiding execution back on track when she acknowledged that state law could allow the case to be retried because “strong” new evidence had emerged.

Her helpful intervention drew gasps from the audience and a stuttering response from Antonin Scalia, the most conservative of the nine justices and a fierce defender of the death penalty, who demanded that Burton repeat what she had just said.

“Well, that’s the end of it, isn’t it?” asked justice Stephen Breyer when she did.

“It is. It is the end of it,” Burton replied. “As much as I would like it to be [otherwise], when you have new evidence, such as in this case – and it is strong evidence – that the court feels like it has to look at, then you are beyond the [relevant legal] bar.”

The strong new evidence came in the form of notes taken by prosecutors when they were deciding which potential jurors to strike off the jury, which revealed they had designated all African Americans on the list with a “B” against their name.

Of the six jurors marked “definite no” by prosecutors, five were African American, while the only white person struck off the list had a declared opposition to the death penalty so should not have been included anyway.

Other black jurors were struck off for false reasons, such as misunderstood religious beliefs, or factors such as age that were not applied to white jurors.

The defence team argued the notes amounted to an “arsenal of smoking guns” and said it was vital that the supreme court reinforce its ruling in an earlier test case – Batson v Kentucky – which requires prosecutors to demonstrate that race is not the motive for striking off minorities from the jury.

“If this court, as it said so many times, is engaged in unceasing efforts to end race discrimination in the criminal courts, then strikes motivated by race cannot be tolerable,” said Bright.

Once the procedural discussions were concluded, a majority of justices appeared to side with Foster, suggesting he may yet have his death sentence overturned and a retrial ordered.

“Isn’t this as clear a Batson violation as the court is ever going to see?” said justice Elena Kagan.

Breyer claimed “any reasonable person looking at this” would agree that prosecutors were looking to “discriminate on the basis of race” when they removed all the black candidates from the jury.

The state of Georgia argues that the notes made by its prosecutors were merely a sign that they were aware of the sensitivity of dismissing black jurors and wanted to take extra care to record the non-racial reasons for their decision.

But Foster’s appeal rests on the argument that many of the reasons subsequently given by prosecutors do not stand up to close scrutiny and left him with a jury less likely to consider crucial mitigating factors such as alleged learning difficulties when deciding on his sentence.

Justice Scalia argued it should be left up to the original trial court to determine whether the prosecutors had passed the so-called “Batson test” by coming up with valid reasons.

“Surely it is the judge that hears the testimony who is best able to judge whether asserted reasons are phony reasons or not,“ he said.

The case also still faces some of the potential procedural hurdles first raised by chief justice Roberts and will decided upon by the supreme court next year.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion